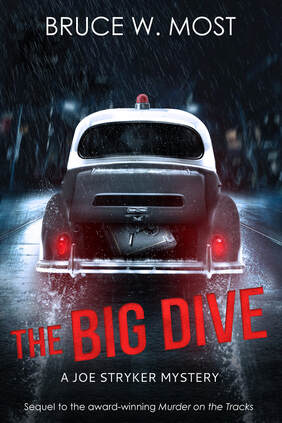

The Big Dive

When Joe Stryker's partner is brutally slain in the line of duty--almost in front of his eyes--two baffling questions face Joe: How did the killer pull off such a brazen murder and escape? And why was his partner—a man so by-the-book that fellow cops scornfully nicknamed him “Saint Benedict”—murdered in the middle of burglarizing a pawnshop?

To protect his dead partner’s reputation—and save his own career—Joe lies to investigators and his wife as he operates in the shadows to discover the truth behind the unexplainable. All while dodging a homicide detective hell-bent to pin the crimes on Joe. Before he can answer the baffling questions and track down the brutal killer, Joe once again must risk his career, his marriage . . . and his life.

To protect his dead partner’s reputation—and save his own career—Joe lies to investigators and his wife as he operates in the shadows to discover the truth behind the unexplainable. All while dodging a homicide detective hell-bent to pin the crimes on Joe. Before he can answer the baffling questions and track down the brutal killer, Joe once again must risk his career, his marriage . . . and his life.

|

|

Chapter 1

Denver is still a nickel town, the way I figure it. Maybe Chicago or Boston can get away with jacking the price of a tune from a nickel to a dime, but I sure as hell ain’t gonna drop a dime to hear Frankie Laine warble “Mule Train.”

I plugged in my nickel and punched B4 on the Wurlitzer, a glowing red, green, and blue monster bigger than the front end of a beer truck. Billie Holiday came on singing “Tain’t Nobody’s Business if I Do.” I returned to the counter at Al’s Diner, adjusted my Sam Browne belt, and settled on the stool next to my shift partner. He didn’t act any more sociable than when I’d left. One of his meaty hands stirred his untouched coffee, the spoon clinking against the cup.

Benedict Greene had been staring into his coffee for weeks now, chewing on something. He was more sullen than usual tonight—edgy, too, as if whatever was on his mind was coming to a boil.

This wasn’t his pattern. We’d partnered for the past five months, and I’d known him several years before that. He’s an upbeat guy by nature, which is something considering he’s a cop. Then again, the war shadows Benedict like it does many of us. He’d fought in the bloody Battle of the Bulge in the snowy forests of Belgium. Perhaps those nightmares had returned to haunt him. God knows, the war still haunts me.

I considered asking what was gnawing on him, but figured it wasn’t my place. Only civilians and rookie cops ask where they have no call to ask. If it were my place to know, Benedict would tell me. Good partners are that way. If something is worth telling, they’ll tell each other before they tell anyone else, even their wives.

So I left him stirring his coffee and reread the shocking black headline plastered on the front page of a well-thumbed copy of the morning Rocky Mountain News.

Truman Fires MacArthur

The bony finger of the fry cook appeared and tapped the newspaper. “The Taft folks are talking impeachment,” he said approvingly behind his stained white apron as Billie sang the blues. “Put Truman in jail with them Rosenbergs.”

If I should take a notion

To Jump into the ocean

Ain’t nobody’s business if I do

No, it wasn’t a smart move, firing a war hero like Douglas MacArthur. The Tafties were itching to impeach Harry Truman and now was their shot.

Not that I blamed the hat man for firing the general. Sure, we need to stand tough against the commies, but the general wanted to invade China, for god’s sake. Against his president’s orders. Sounded like a nightmare to me. MacArthur had been disloyal to his own commander, and I detested disloyalty.

On the other hand, I wasn’t buying into this limited “police action” crap. Hell, we could be bogged down in those bloody Korean hills forever.

War and life were clearer back when Benedict and I fought in the Big One. We had a well-defined mission: kick the Little Corporal’s ass to hell, along with his puppets in Italy and Japan. Nothing limited about what we were doing. Unconditional surrender or die. But in Korea, all we seemed to be fighting for was a dumb line on a map.

Maybe the Tafties were right. Foreign wars were like the measles. Something you got over as quickly as possible.

I swear, I won’t call no copper

If I’m beat up by my papa

Ain’t nobody’s business if I do

I finished my coffee. We’d taken our short five long enough. Time to get back to the streets. I stood to leave. Benedict glanced at his watch for the umpteenth time tonight and rose. His coffee remained untouched, but he slid a nickel under his saucer. He always paid for his coffee. No self-respecting cop pays for his coffee. It’s an unwritten code on the street. But that was Benedict for you. “Saint Benedict,” cops called him behind his back. A regular choirboy. He never took free meals, cut-rate car repairs, free cigs to smoke or sell, juice from bookies and bondsmen—the harmless goodies that keep hardworking, underpaid cops and their families above water. He always made me feel a little guilty for not paying for my coffee. But someone needed to make the barkeeps, tamale vendors, and shop owners feel they were getting a little extra protection, an extra rattle on their doorknobs, in turn for a free bottle of milk for the kids or a hot tamale on a bitter January night.

I shrugged toward the fry cook in apology for my partner’s saintly behavior, and we hit the streets in our patrol car, a black three-year-old Ford already on its last legs. Benedict drove, a half-smoked Old Gold clamped in the middle of his lips, as we crawled deeper into Five Points, what the locals called the “Harlem of the West.” We passed the Roxy theater, its marquee glittering as a handful of Negroes lined up to watch “Destry Rides Again.” Being a Wednesday, the street wasn’t crowded, but on weekends there was no room to walk on the sidewalks. We passed blocks of stately Victorian homes owned by doctors rubbing elbows with row houses owned by Pullman Porters. The sad sounds of jazz drifted out of the Ex-Servicemen’s Club.

Benedict took in none of this. His eyes stared dead ahead, never glancing to either side, never scouring car tags for hot heaps or faces for wants. An asshole could have been jack-rolling a drunk for shoes and change, and Benedict would have missed it.

Luckily, the April twilight was crisp and dry, keeping down the tempers on the streets and in the backrooms. Just the usual barflies, monte men, and hookers drifting in and out of the pool halls and jazz joints, their dark faces scowling at us as we passed. A beer bottle shattered on the sidewalk. Two men argued over a raggedy coat. The usual.

At 9:14, we caught a call of a female screaming in one of the newer two-story brick-faced projects on Stout. A Mexican gandy dancer had been fired by Burlington Railroad and was taking it out on a bottle of cheap gin and his overweight wife. By the time we arrived, the bottle was empty and the wife insisted life was just peachy, despite a right eye resembling something worked over by Jake LaMotta. She must have been listening to Billie Holiday.

Benedict returned to the patrol car while I hung around the building for a few minutes, picking up skinny and handing a family a sawbuck that a gin mill owner juiced me with the previous night. When I returned to the car, Benedict had already filled out the log sheet fastened to a clipboard and was scribbling in his dime-store pocket notebook. He never told me what he wrote in his brown notebook. Names of snitches. A grocery list. Poetry for all I knew.

He glanced at his watch, again, as if he had somewhere more important to be.

We took a smoke break with another cruiser from Precinct 52 behind K. K. Miyamoto’s Fine Photography studio. Later, cruising by the dark, silent South Platte river bottom, among the warehouses and railroad tracks, Benedict finally got around to speaking what was on his mind.

“We got this little deal goin’, Joe,” he said in a low voice, with another glance at his watch.

When he didn’t say anything more, I said, “Whattya mean, a little deal?”

“Something we thought you’d wanna be part of. There’s some scratch in it for you.”

“From this deal?”

“Yeah.”

“So what’s the deal?” I pressed.

“It’s kinda hard to explain.”

“Try me, Benedict. I’m a bright guy.”

He fell silent. I came at it from a different angle. “Who’s ‘we’?”

“Some guys.”

“What guys?”

“You know, our kind.” It was as if he were digging for words in a junk drawer.

“Cops?”

“I’m not explaining this well.”

“Shit, Benedict, you ain’t explaining it at all.”

“Lemme show you, Joe. You’ll understand after I show you.”

He drove us several blocks to a dark alley between Arapahoe and Curtis. As we eased into the alley, he doused the headlights, rolled down his window, and listened as we crept through the narrow canyon between the backs of small, tired businesses. Grit and broken glass crunched under the tires. A third of the way, Benedict stopped and flicked on the spotlight. Its beam snared a junkyard dog rooting in an overturned rusty barrel. The dog yanked its head out. A white sack muzzled its snout. It glared at us, sick yellow eyes glistening in the spotlight, holding them on us before slinking off into the darkness, the sack still clinging to its snout.

Benedict drove on before stopping mid alley between a furniture store and a pawnshop. The furniture store looked fine on my side, but the security light above the rear door of the pawnshop was busted out. Benedict painted the spotlight across the building, snaring barred windows, a No Parking sign, peeling paint, and a heavy door with a small grimy window. Above the window, white lettering spelled out

Lennie’s Loan and Music Co.

Use Front Entrance

“You got a tip about Lennie’s?” I said. “Half the shit he sells is stolen.”

My partner’s eyes were large and jittery. “That’s the beauty of it.”

“The beauty of what?”

He killed the spotlight, drove a few feet beyond the door, and stopped.

“See something?” I said.

“Wait here.” He slid out and eased his door closed. He walked behind the car to the pawnshop. Normally, Benedict walked stiffly, spine erect, trying to appear taller than he was. Now he walked with his back hunched, his muscular shoulders rolled up tight, his head glancing side to side. He looked small in the alley.

I peered out the rear window. The pawnshop door was ajar. I scrambled out of the car, the interior light spilling into the empty alley, highlighting me like a target. I eased the door shut.

“Benedict—the door,” I half-whispered.

He stopped and waved me off.

“Someone’s busted into the place,” I said.

“Don’t worry about it,” his voice low but not hushed.

“What do you mean, don’t worry?”

“Trust me.”

He merged into the shadows of the pawnshop and pulled the door farther open. Hinges screeched like lost souls. He scanned the alley in both directions.

I plugged in my nickel and punched B4 on the Wurlitzer, a glowing red, green, and blue monster bigger than the front end of a beer truck. Billie Holiday came on singing “Tain’t Nobody’s Business if I Do.” I returned to the counter at Al’s Diner, adjusted my Sam Browne belt, and settled on the stool next to my shift partner. He didn’t act any more sociable than when I’d left. One of his meaty hands stirred his untouched coffee, the spoon clinking against the cup.

Benedict Greene had been staring into his coffee for weeks now, chewing on something. He was more sullen than usual tonight—edgy, too, as if whatever was on his mind was coming to a boil.

This wasn’t his pattern. We’d partnered for the past five months, and I’d known him several years before that. He’s an upbeat guy by nature, which is something considering he’s a cop. Then again, the war shadows Benedict like it does many of us. He’d fought in the bloody Battle of the Bulge in the snowy forests of Belgium. Perhaps those nightmares had returned to haunt him. God knows, the war still haunts me.

I considered asking what was gnawing on him, but figured it wasn’t my place. Only civilians and rookie cops ask where they have no call to ask. If it were my place to know, Benedict would tell me. Good partners are that way. If something is worth telling, they’ll tell each other before they tell anyone else, even their wives.

So I left him stirring his coffee and reread the shocking black headline plastered on the front page of a well-thumbed copy of the morning Rocky Mountain News.

Truman Fires MacArthur

The bony finger of the fry cook appeared and tapped the newspaper. “The Taft folks are talking impeachment,” he said approvingly behind his stained white apron as Billie sang the blues. “Put Truman in jail with them Rosenbergs.”

If I should take a notion

To Jump into the ocean

Ain’t nobody’s business if I do

No, it wasn’t a smart move, firing a war hero like Douglas MacArthur. The Tafties were itching to impeach Harry Truman and now was their shot.

Not that I blamed the hat man for firing the general. Sure, we need to stand tough against the commies, but the general wanted to invade China, for god’s sake. Against his president’s orders. Sounded like a nightmare to me. MacArthur had been disloyal to his own commander, and I detested disloyalty.

On the other hand, I wasn’t buying into this limited “police action” crap. Hell, we could be bogged down in those bloody Korean hills forever.

War and life were clearer back when Benedict and I fought in the Big One. We had a well-defined mission: kick the Little Corporal’s ass to hell, along with his puppets in Italy and Japan. Nothing limited about what we were doing. Unconditional surrender or die. But in Korea, all we seemed to be fighting for was a dumb line on a map.

Maybe the Tafties were right. Foreign wars were like the measles. Something you got over as quickly as possible.

I swear, I won’t call no copper

If I’m beat up by my papa

Ain’t nobody’s business if I do

I finished my coffee. We’d taken our short five long enough. Time to get back to the streets. I stood to leave. Benedict glanced at his watch for the umpteenth time tonight and rose. His coffee remained untouched, but he slid a nickel under his saucer. He always paid for his coffee. No self-respecting cop pays for his coffee. It’s an unwritten code on the street. But that was Benedict for you. “Saint Benedict,” cops called him behind his back. A regular choirboy. He never took free meals, cut-rate car repairs, free cigs to smoke or sell, juice from bookies and bondsmen—the harmless goodies that keep hardworking, underpaid cops and their families above water. He always made me feel a little guilty for not paying for my coffee. But someone needed to make the barkeeps, tamale vendors, and shop owners feel they were getting a little extra protection, an extra rattle on their doorknobs, in turn for a free bottle of milk for the kids or a hot tamale on a bitter January night.

I shrugged toward the fry cook in apology for my partner’s saintly behavior, and we hit the streets in our patrol car, a black three-year-old Ford already on its last legs. Benedict drove, a half-smoked Old Gold clamped in the middle of his lips, as we crawled deeper into Five Points, what the locals called the “Harlem of the West.” We passed the Roxy theater, its marquee glittering as a handful of Negroes lined up to watch “Destry Rides Again.” Being a Wednesday, the street wasn’t crowded, but on weekends there was no room to walk on the sidewalks. We passed blocks of stately Victorian homes owned by doctors rubbing elbows with row houses owned by Pullman Porters. The sad sounds of jazz drifted out of the Ex-Servicemen’s Club.

Benedict took in none of this. His eyes stared dead ahead, never glancing to either side, never scouring car tags for hot heaps or faces for wants. An asshole could have been jack-rolling a drunk for shoes and change, and Benedict would have missed it.

Luckily, the April twilight was crisp and dry, keeping down the tempers on the streets and in the backrooms. Just the usual barflies, monte men, and hookers drifting in and out of the pool halls and jazz joints, their dark faces scowling at us as we passed. A beer bottle shattered on the sidewalk. Two men argued over a raggedy coat. The usual.

At 9:14, we caught a call of a female screaming in one of the newer two-story brick-faced projects on Stout. A Mexican gandy dancer had been fired by Burlington Railroad and was taking it out on a bottle of cheap gin and his overweight wife. By the time we arrived, the bottle was empty and the wife insisted life was just peachy, despite a right eye resembling something worked over by Jake LaMotta. She must have been listening to Billie Holiday.

Benedict returned to the patrol car while I hung around the building for a few minutes, picking up skinny and handing a family a sawbuck that a gin mill owner juiced me with the previous night. When I returned to the car, Benedict had already filled out the log sheet fastened to a clipboard and was scribbling in his dime-store pocket notebook. He never told me what he wrote in his brown notebook. Names of snitches. A grocery list. Poetry for all I knew.

He glanced at his watch, again, as if he had somewhere more important to be.

We took a smoke break with another cruiser from Precinct 52 behind K. K. Miyamoto’s Fine Photography studio. Later, cruising by the dark, silent South Platte river bottom, among the warehouses and railroad tracks, Benedict finally got around to speaking what was on his mind.

“We got this little deal goin’, Joe,” he said in a low voice, with another glance at his watch.

When he didn’t say anything more, I said, “Whattya mean, a little deal?”

“Something we thought you’d wanna be part of. There’s some scratch in it for you.”

“From this deal?”

“Yeah.”

“So what’s the deal?” I pressed.

“It’s kinda hard to explain.”

“Try me, Benedict. I’m a bright guy.”

He fell silent. I came at it from a different angle. “Who’s ‘we’?”

“Some guys.”

“What guys?”

“You know, our kind.” It was as if he were digging for words in a junk drawer.

“Cops?”

“I’m not explaining this well.”

“Shit, Benedict, you ain’t explaining it at all.”

“Lemme show you, Joe. You’ll understand after I show you.”

He drove us several blocks to a dark alley between Arapahoe and Curtis. As we eased into the alley, he doused the headlights, rolled down his window, and listened as we crept through the narrow canyon between the backs of small, tired businesses. Grit and broken glass crunched under the tires. A third of the way, Benedict stopped and flicked on the spotlight. Its beam snared a junkyard dog rooting in an overturned rusty barrel. The dog yanked its head out. A white sack muzzled its snout. It glared at us, sick yellow eyes glistening in the spotlight, holding them on us before slinking off into the darkness, the sack still clinging to its snout.

Benedict drove on before stopping mid alley between a furniture store and a pawnshop. The furniture store looked fine on my side, but the security light above the rear door of the pawnshop was busted out. Benedict painted the spotlight across the building, snaring barred windows, a No Parking sign, peeling paint, and a heavy door with a small grimy window. Above the window, white lettering spelled out

Lennie’s Loan and Music Co.

Use Front Entrance

“You got a tip about Lennie’s?” I said. “Half the shit he sells is stolen.”

My partner’s eyes were large and jittery. “That’s the beauty of it.”

“The beauty of what?”

He killed the spotlight, drove a few feet beyond the door, and stopped.

“See something?” I said.

“Wait here.” He slid out and eased his door closed. He walked behind the car to the pawnshop. Normally, Benedict walked stiffly, spine erect, trying to appear taller than he was. Now he walked with his back hunched, his muscular shoulders rolled up tight, his head glancing side to side. He looked small in the alley.

I peered out the rear window. The pawnshop door was ajar. I scrambled out of the car, the interior light spilling into the empty alley, highlighting me like a target. I eased the door shut.

“Benedict—the door,” I half-whispered.

He stopped and waved me off.

“Someone’s busted into the place,” I said.

“Don’t worry about it,” his voice low but not hushed.

“What do you mean, don’t worry?”

“Trust me.”

He merged into the shadows of the pawnshop and pulled the door farther open. Hinges screeched like lost souls. He scanned the alley in both directions.