|

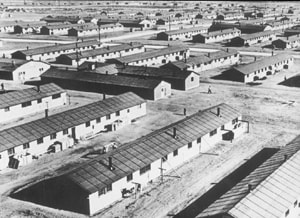

Surrounded by barbed wire, machine-gun towers, and armed military police, what was life like for the 120,000 ethnic Japanese incarcerated inside the ten relocation camps? Or concentration camps as I suggested in an earlier blog.  n this and the next blog, I’ll take you inside the camps. How many people did they hold, how were the camps laid out, what facilities were built? What were the living quarters like? What did the prisoners do with their days? What freedoms did they have? And not have? Because Camp Amache is most familiar to me due to its key role in The Big Dive, I’ll focus on it. But life was pretty similar in the other nine camps in the west and Arkansas. The government built Camp Amache near the small community of Granada in southeastern Colorado. Hence its formal name, Granada Relocation Center. Amache came from the name of a Cheyenne chief’s daughter, the wife of the man after whom the local county was named, John Prowers. The camp incorporated roughly 10,000 acres. Only 640 acres—a square mile—went to residential, community and administrative buildings. The remaining land was designated for agricultural use, as the internees had to raise much of their own food. Interestingly, Amache was the only one of the ten camps built on private land. The federal government bought or condemned land owned by local ranchers and farmers, which engendered much resentment. Camp Amache received its first internees on August 27, 1942. Most of the internees came from California. Like all internees, they were first processed through “assembly centers” along the West Coast, then transferred to the permanent concentration camps. Camp Amache remained in operation until October 1945. During those three years, 10,000 Japanese passed through, with a peak population of 7,318 in February 1943. That made it the tenth largest town in Colorado. Yet it was the smallest of the ten camps created and administered by the federal War Relocation Authority (WRA) set up expressly to “evacuate,” relocate, and imprison the Japanese—most of whom were U.S. citizens.  Inferior Camp Construction Construction of the camp began a mere two months before the first internees arrived, leaving much unfinished or poorly constructed. Water had to be trucked in from Granada. The internees helped the WRA finish the buildings or improve them as best they could. As the top picture illustrates, the camp was a sprawl of barrack-like structures built on concrete foundations. Twelve barracks formed a block, and the camp contained 39 blocks. Each barrack consisted of six rooms, varying in size from 16 x 20 to 20 x 24. Families as large as seven were assigned to the larger rooms, though in reality more than seven often occupied a single room. The thin-walled wooden barracks were uninsulated, with floors of loose bricks set in dirt. The exterior walls and roof were tar-papered. The barracks were so rudimentary, the army considered it “theater of operations” housing, fit only for soldiers on a temporary basis. Coal-burning stoves produced the only heat, which wasn’t enough to protect against the harsh winter. As most internees came from California, few owned winter clothing. But as cold as Camp Amache got, it was not as bad as Heart Mountain camp in Wyoming, where temperatures plummeted to 30 below. The rooms came unfurnished except for cots, thin mattresses, and quilts. The Japanese fashioned what crude furniture they could from scrap lumber. They hung partitions made from sheets for privacy. The rooms had a single light bulb and no running water. In addition to the living quarters, each block contained a mess hall, bathhouse, recreation hall, and laundry facilities. The rest of the camp included a 150-bed hospital, schools, post office, stores, warehouses, administrative buildings, police and fire departments, and living quarters for military police and non-internee civilians. When finished, the camp had 560 buildings. In the next post, I’ll describe what daily life was like for Camp Amache prisoners in their barbed-wired world.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Bruce Most is an award-winning mystery novelist and short-story writer. His latest novel, The Big Dive, is the sequel to the award-winning Murder on the Tracks, which features a street cop seeking redemption while investigating a string of murders in 1949 Denver. His award-winning Rope Burn involves cattle rustling and murder in contemporary Wyoming ranch country. Bonded for Murder and Missing Bonds features feisty Denver bail bondswoman, Ruby Dark. Archives

February 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed