|

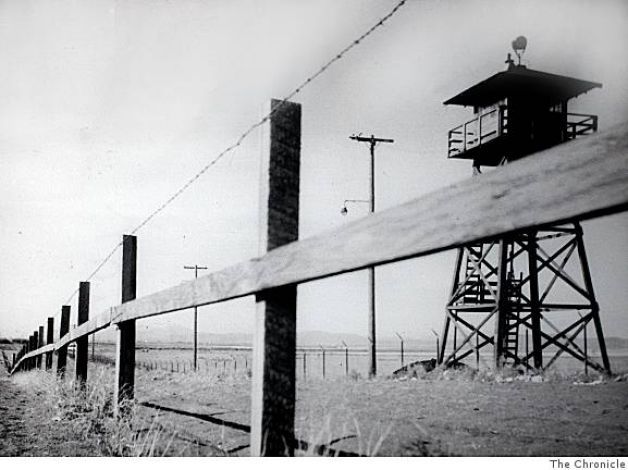

The charged phrase has dramatically reentered the American lexicon. Some critics of the detention centers for illegal immigrants and asylum seekers on our southern borders describe the facilities as “concentration camps.” To make their point, they often compare the facilities to the Japanese-American “concentration camps.” Regardless of your view of the current border facilities, I thought it might be interesting to examine exactly what the 1940s camps were: relocation camps, prisons, internment camps, incarceration camps, concentration camps? Most of the relocation camps were built in inhospitable country: barren land, hot in the summer and cold in the winter. Camp Amache, an important plot thread in my historical mystery The Big Dive, was built in southeast Colorado. The prairie land is arid. Temperatures rocket over 100 degrees in summer and produce snowstorms in winter. Not a pleasant place to live in thin-walled barracks. “The main thing you remembered was the dust, always the dust,” recalled a former prisoner of another camp, Manzanar, in Inyo County, California, near the eastern Sierra Mountains. Of course, Americans voluntarily live in inhospitable areas. Whatever you call the camps, however, there was nothing voluntary about them. They were enclosed by barbed wire and guarded by military police in gun towers with searchlights and heavy machine guns. You could not permanently leave unless you joined the U.S. military (more on that in a later blog) or took critical skilled or professional jobs in the Midwest or East Coast. Babies were born in the camps. People died and were buried in the camps. A prison? No. None of its residents had been charged with a crime, convicted, and sentenced to these camps. They’d been rounded up solely because of their Japanese ancestry. President Franklin Roosevelt’s executive order 9066 was clear in its intent to establish these camps out of (unfounded) fear of sabotage by ethnic Japanese living in the western United States. But the government euphemistically called them relocation camps, as if they were built for the protection of the “evacuees.” But these were anything but relocation camps. Or summer camps. As one former prisoner noted: “If it was for our protection, why did the guns point inward, rather than outward?” Which brings us to “concentration camp.” That description was used at the time, primarily by critics of the camps. Who were few and far between. One of those few was Colorado Governor Ralph Carr, who protested the placement of a camp in the state: “When it is suggested that American citizens be thrown into concentration camps, where they lose all privileges of citizenship under the Constitution, then the principles of that great document are violated and lost.” Use of concentration camp has become more common in recent years as histories are written and exhibits mounted about the Japanese-American camps. And as the intensity of current political debate rises.  Concentration Camp a Loaded Word Today Dictionaries generally define concentration camps as places where large groups of civilians, usually political prisoners or members of ethnic or religious minorities, are confined under harsh conditions. Use of the term goes back to the 1890s. Many countries built them over the ensuing decades, before and after the Nazis. Think Soviet Gulag, or Vietnam and China “re-education camps.” The problem today is that concentration camp has been a charged phrase since the Third Reich. Its use by Gov. Carr and others during the war was not surprising. At the time, our nation knew little to nothing of the horrors of the Nazi camps. Many people now feel we should never use the word except to refer to the Nazi camps. The counter-argument is that the Nazi camps never served as concentration camps. They were death or extermination camps for Jews and other “undesirables.” As wrong as the Japanese-American relocation camps were, they were never designed to exterminate a group of people. A few Americans still insist the relocation camps were necessary and not inhuman. Said a woman in a 2007 newspaper article who lived near Camp Amache: “They call it a concentration camp. It wasn't a concentration camp; it was a relocation center. It was a lot safer place for them.” I strongly disagree. To me, the Japanese-American relocation camps, or “internment camps” as they were euphemistically called, fit the definition of concentration camp. What’s your opinion: relocation camp, concentration camp, internment camp, summer camp?

5 Comments

Harry Postlethwait

7/31/2019 05:05:11 pm

I had a friend in our optimist club in the 1980's who was a young child (toddler) who lived with his parents in the Colorado "relocation" concentration camp. Unfortunately, I've lost contact with Ned and have found no social media contacts.

Reply

Bruce W. Most

7/31/2019 07:18:10 pm

Thanks, Harry. Some remained in the area after the camp was closed, so I imagine there are similar stories among people in Colorado.

Reply

Terri Mabon

8/4/2019 09:20:09 am

I recently read "Bridge of Scarlet Leaves" by Kristina McMorris, another book reminding us of our "own country's prejudices".

Reply

Bruce Most

7/26/2023 10:06:27 am

Thanks, Jonah. It's a black stain on American history we should never forget.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Bruce Most is an award-winning mystery novelist and short-story writer. His latest novel, The Big Dive, is the sequel to the award-winning Murder on the Tracks, which features a street cop seeking redemption while investigating a string of murders in 1949 Denver. His award-winning Rope Burn involves cattle rustling and murder in contemporary Wyoming ranch country. Bonded for Murder and Missing Bonds features feisty Denver bail bondswoman, Ruby Dark. Archives

February 2022

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed